As children, many imagined that reading minds would be the ultimate superpower. In pharmacy practice, leaders may at times wish for those same abilities.

Introduction

As children, many imagined that reading minds would be the ultimate superpower. In pharmacy practice, leaders may at times wish for those same abilities. The capacity to understand what their staff are truly thinking, to uncover what lies beneath the surface of their behaviour or what they really mean while talking around points in conversations. While these powers do not exist in the literal sense, emotional intelligence provides a human equivalent.

Emotional intelligence (EI) enables leaders to correctly anticipate the needs of colleagues, offer meaningful support, and consider perspectives that differ from their own. In doing so, emotional intelligence helps to dismantle barriers and open space for conversations, whether challenging, inspiring, or routine. Unlike imaginary superpowers, these abilities are not bestowed by chance; they are cultivated over time, strengthened like a muscle and refined through deliberate practice.

This article examines how emotionally intelligent leadership skills enhance communication and contribute to improved outcomes for individuals, teams, pharmacies, and ultimately, patients 1.

What is emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence is a set of skills that help us perceive, understand, express, reason with, and manage emotions both in ourselves and others1. These skills help people to effectively work with others, connect, collaborate, and communicate. They help expand perspective and equip people with the skills to become solution-focused and think creatively, laterally and innovate. This improves the quality of one’s performance 1.

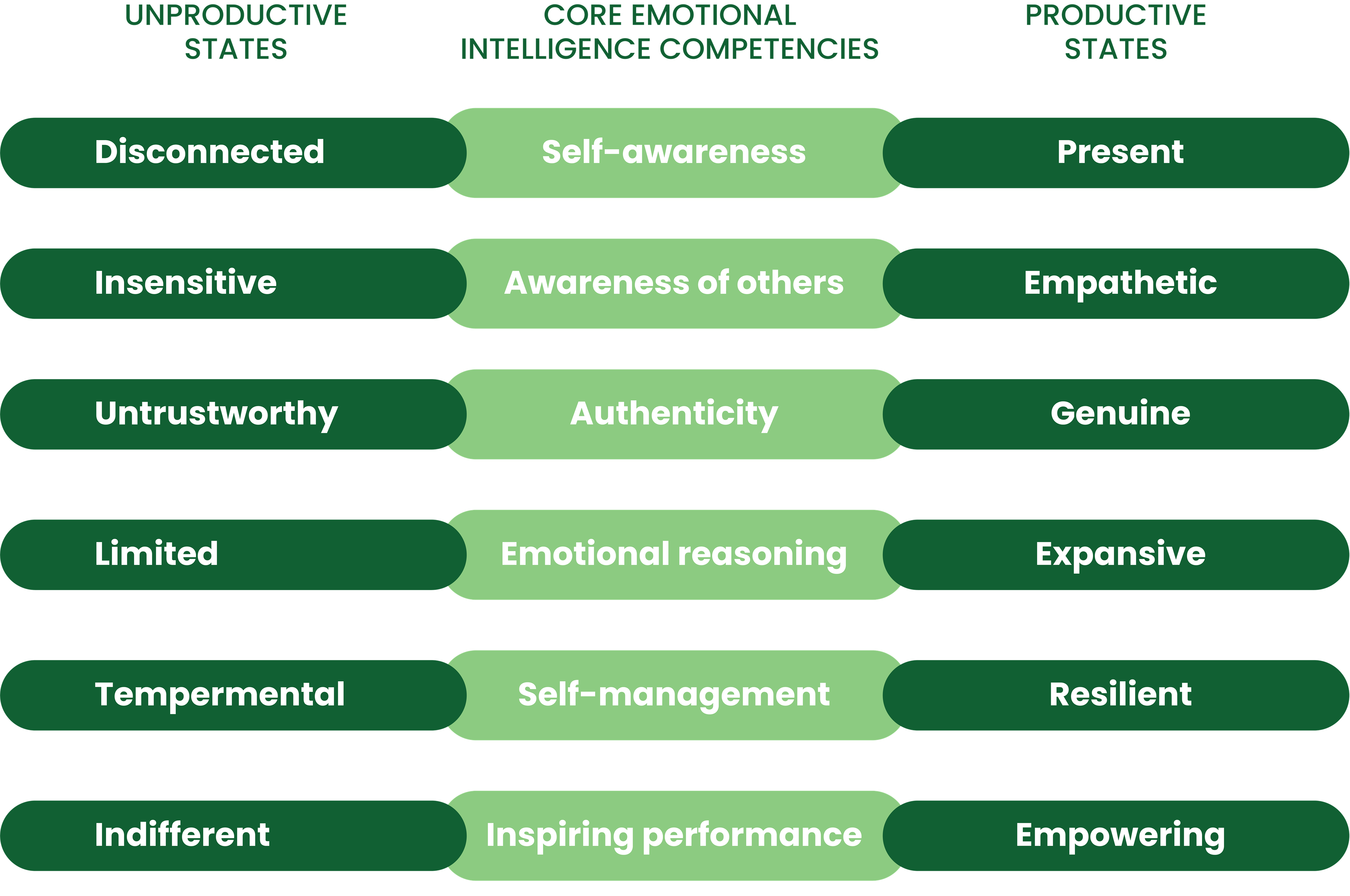

While there are many emotional intelligence models, the one explored in this article is the Genos Model of Emotional Intelligence, a behaviour-based model that has identified there are six core competencies:

Self-awareness

The ability to be aware of the behaviour one demonstrates, their strengths and limitations and the impact they have on others 1.Awareness of othersNoticing and acknowledging others, ensuring others feel valued and adjusting one’s leadership style to best fit with others 1.

Authenticity

Openly and effectively expressing oneself, honouring commitments and encouraging this behaviour in others. It also involves appropriately addressing feelings at work, such as happiness and frustration, providing feedback to colleagues about the way they feel and expressing emotions at the right time, to the right degree to the right people 1.

Emotional reasoning

The ability to use emotional information (from oneself and others) and combining it with other facts and information when decision making 1.

Self-management

Managing one’s own mood and emotions, time and behaviours and continuously improving oneself 1.

Inspiring performance

Facilitating high performance in others through problem solving, promoting, recognising and supporting others’ work. This goes beyond ‘compliance’ style performance indicators, which fail to drive discretionary effort, and shifts to a more inspiring style to empower others to perform above and beyond what is expected of them 1.

As shown in figure 1, if demonstrated more often, these competencies enable people to be the productive being states of present, empathetic, genuine, expansive, resilient and empowering. This is in direct contrast to if emotional intelligence core competencies are not demonstrated. When not demonstrated, people shift to be the unproductive being states, disconnected, insensitive, untrustworthy, limited, temperamental and indifferent 1.

Dialling in on the competency ‘Awareness of Others’ allows leaders the greatest gains when wanting to improve communication and performance.

Awareness of others 1

Awareness of others is underpinned by seven behaviours:

- Makes others feel appreciated

- Adjusts their style so that it fits well with others

- Notices when someone needs support and responds effectively

- Accurately views situations from the perspective of others

- Acknowledges the views and opinions of others

- Accurately anticipates responses or reactions from others

- Balances achieving results with others’ needs

When these behaviours are demonstrated more often, we become more empathetic. Empathy, the ability to understand and share in another’s feelings. It is important to note this does not necessarily mean agreement, rather respect and understanding. As humans, this can be hard, and as leaders, it imposes an inherent challenge.

Everyone has different values that drive their behaviours. Support to one can be a hindrance or undermining to another. Understanding the drivers of personalities simplifies this challenge and allows leaders to support staff more effectively while minimising the guesswork.

Understand personalities

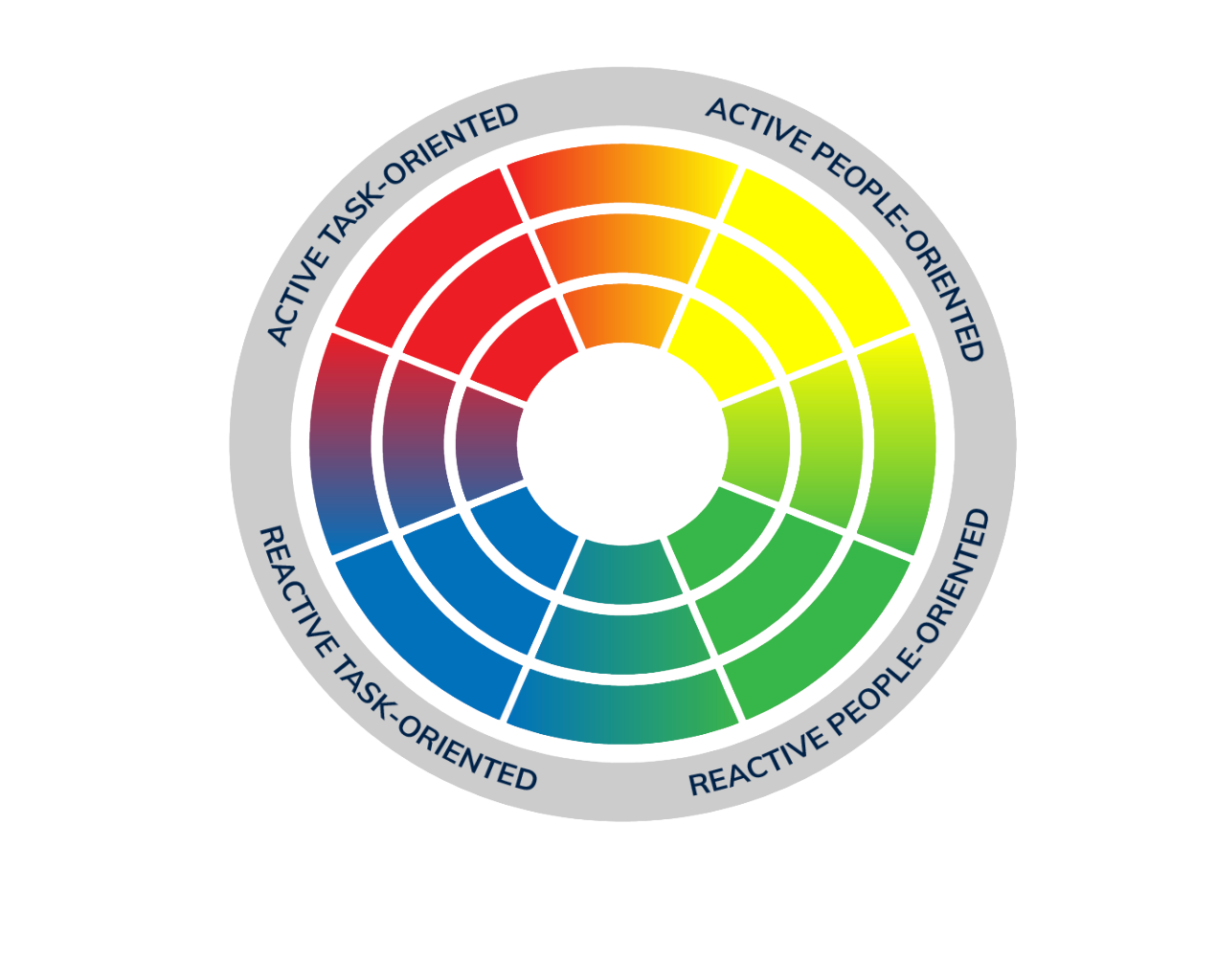

Research shows that 60-80% of all problems in workplaces are due to a clash of values, personalities and leadership challenges 2. Acknowledging the impact different personalities have in workplaces is the first step towards adapting one’s style to suit the needs of others. To enable such flexibility, leaders need to understand how people’s personalities and cultural backgrounds influence what, how and why they communicate and behave the way they do 2. The Global DISC Framework (fig 2) of cultural intelligence explains this further. Cultural intelligence by their definition, is the ability to see the same situations from different perspectives to make better decisions and choose to respond instead of reacting 3.

The model identifies that there are four personality types.

Active Task-Oriented, Reactive Task-Oriented, Active People-Oriented, Reactive People-Oriented 4.

Active vs reactive personality types

Dissecting the Global DISC wheel (fig 2) horizontally, a distinction emerges between active and reactive orientations. Individuals on the top half of the wheel are described as active. This orientation is often associated with being extroverted, outgoing, and fastpaced. Active individuals speak and move quickly, typically coming across as confident and energetic. They are enthusiastic starters of new projects and comfortable with change. Their decision-making tends to be quick, sometimes impulsive, and they are highly responsive to whatever is happening around them, including conflict. This makes them positive, adaptable, and dynamic, though at times less consistent in follow-through 5.

In contrast, those on the bottom half of the wheel display a reactive orientation. They are more reserved, moderate-paced, and often introverted. Reactive individuals prefer to take their time, carefully considering decisions and weighing risks before acting. They may appear cautious or hesitant, and while they are less likely to initiate new projects, they are highly reliable at completing what they begin. They value stability and consistency, generally preferring to follow established rules. Their calm, focused, and measured approach means they are less easily distracted, though they may resist change and struggle to express their own needs directly 5.

Task-oriented vs people oriented personality types

Dissecting the wheel vertically, a different distinction emerges between task-oriented and people-oriented individuals. Task-oriented individuals prefer working with tasks, concepts, and numbers. They often plan ahead and gain satisfaction from developing and implementing processes. Analytical by nature, they devote their full attention to the task at hand, typically avoiding socialising while working. They approach situations logically, question the accuracy of information, and may appear judgmental or critical of others’ behaviours. Because their priority is task completion, they may give less weight to “soft” emotions and, at times, come across as distant or unfriendly 5.

Conversely, the right side of the wheel reflects people-oriented behaviours. People-oriented individuals are energised by social interaction and thrive on building and maintaining relationships. They are more accepting of others’ behaviours and perspectives, often caring deeply for colleagues, friends, family, and even strangers. They are approachable, easy-going, and emotionally expressive, drawing satisfaction from collaboration and helping others. Their warmth, humour, and friendliness make them natural “people pleasers.” However, because they prioritise relationships, task completion can sometimes become secondary, leading to perceptions of disorganisation or lack of focus 5.

By combining these orientations, we achieve the four primary personality types of the model. Most people can be identified by one dominant personality style, though it is likely that their personality will be a culmination of two or more. Table 1 shows the hallmarks of each personality type, what they value and how to identify them.

| Style | How they communicate & behave | What they value | How to identify them | Tips for communicating with them |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Task-Oriented | Direct, assertive, decisive, fast-paced; focus on results; may come across as blunt or impatient. | Winning, achievement, efficiency, autonomy, risk-taking. | Busy environment, achievement driven, will talk about wins, display awards; confident body language; will put up a fight in conflict. | Be concise, focus on outcomes, provide facts and highlights; don’t waste their time; acknowledge achievements. |

| Reactive Task-Oriented | Reserved, precise, analytical; focus on detail, accuracy, and logic; risk-averse; may appear critical or cautious. | Quality, accuracy, process, rules, reliability. | Organised and structured desk; formal setting; emphasis on systems and data; becomes stubborn in conflict. | Provide written data and rationale; allow time to decide; respect their need for accuracy; avoid emotional arguments. |

| Active People-Oriented | Enthusiastic, expressive, talkative; focus on people and ideas; may be impulsive and easily distracted. | Approval, recognition, relationships, fun, change. | Disorganised but “lively” workspace; likes motivational quotes; animated body language; stories; uses humour or sarcasm to lighten stressful situations | Be optimistic and energetic; use stories; involve them in discussions; acknowledge contributions; avoid too much detail. |

| Reactive People-Oriented | Steady, calm, patient; good listeners; focus on harmony and cooperation; may resist change or avoid conflict. | Stability, trust, teamwork, traditions, loyalty | Family photos, comfortable and relational environment; approachable but reserved in groups; Concedes in conflict. | Be sincere and respectful; allow time for trust-building; provide step-by-step instructions; avoid confrontation; show appreciation. |

Practical application: Flexing communication to match personality

Once a leader can identify where there are similarities and differences to their own dominant personality style, they can begin to identify how they can adapt their communication and behaviour to meet the needs of others.

Example 1 – task vs people priorities

A pharmacy manager, who identifies as active and task-oriented, became frustrated with a dispensary technician who was consistently late completing the daily order. From the manager’s perspective, deadlines and task completion are paramount, so the behaviour appeared careless or disorganised.

Using awareness of others, the manager recognised that the technician’s likely style was reactive and people-oriented—valuing patient care, staff relationships, and harmony over immediate task completion. A conversation confirmed this: the technician understood the process but was regularly side-tracked by patient questions and staff interruptions, which she viewed as more important in the moment.

Together, they agreed on an adapted process: the order would be completed at a set time, at a different computer, with team communication that the technician was not to be interrupted. By reframing the issue as a prioritisation conflict between styles, rather than poor performance, the manager preserved the technician’s relational strengths while achieving task consistency.

Example 2 – results vs relationships

A retail manager, who identifies as active and task-oriented, became increasingly frustrated when a reactive, people-oriented senior pharmacy assistant did not engage with a newly launched diabetes service. The manager, focused on achieving KPIs, set clear expectations that every at-risk or diabetic patient should be offered the service and that interactions would be tallied on a score-sheet to track discussions and conversions. Despite repeated explanations, the assistant continued to approach patient care as she had for years, seemingly ignoring the directive.

From the manager’s perspective, this appeared as resistance and underperformance. However, by applying awareness of others, the manager considered the assistant’s personality style. As a reactive, people-oriented team member, the assistant valued long-standing relationships, trust, and patient comfort. She found the tally-sheet process transactional and feared that “selling” the service might compromise the genuine rapport she had built with patients over time.

Instead of enforcing compliance, the manager initiated a conversation to uncover the assistant’s perspective. The discussion confirmed that her hesitation was not due to misunderstanding, but to prioritising patient relationships and trust above KPI-driven processes.

Together, they adapted the approach. The assistant would continue engaging patients in her natural relational style but would record discussions at set points in the day rather than during the interaction itself. The manager also acknowledged her strength in building rapport and framed the service as an extension of patient care, not a sales metric.

By reframing the issue as a values clash rather than refusal, and by flexing communication to align with the assistant’s orientation, the manager acknowledged their strengths and preserved their relationship while ensuring service KPIs could still be tracked and achieved.

Demonstrating other emotional intelligence competencies

By developing awareness of others, leaders naturally strengthen other emotional intelligence competencies, creating a synergistic effect on communication, decision-making, and team performance.

Emotional reasoning, for example, is enhanced because leaders can combine insight into team members’ emotions with objective facts when making decisions. In pharmacy practice, this might involve considering staff workload, patient expectations, and personality differences before introducing a new workflow. Rather than enforcing rigid compliance, the leader can anticipate likely responses, address concerns proactively, and gain buy-in 1.

Similarly, awareness of others supports inspiring performance. Leaders who understand what motivates different personality types can recognise achievements in a way that resonates with each individual. A reactive, people-oriented staff member may value personal acknowledgment and trust, whereas an active, task oriented colleague might respond more strongly to recognition of results and efficiency. Tailoring feedback in this way fosters discretionary effort, enhances morale, and improves retention 1.

Importantly, awareness of others also reinforces authenticity and self-management. Leaders who understand their own emotional triggers can modulate responses in high-pressure situations, while still expressing genuine care and respect for staff. By flexing behaviour based on emotional intelligence insights, leaders transform day-to-day interactions into opportunities for collaboration, growth, and innovation.

In summary, awareness of others is the gateway through which leaders leverage multiple EI competencies, creating a culture that encourages trust, engagement, and high performance across pharmacy teams.

Common pitfalls when awareness of others is absent

While the benefits of emotional intelligence are significant, the absence of “awareness of others” often leads to predictable challenges in pharmacy teams.

Misinterpreting silence as agreement

A team member who is naturally reflective (reactive orientation) may stay quiet in meetings, not because they agree, but because they need time to process information. Without awareness, a leader may assume consensus and later encounter passive resistance or disengagement.

Applying a one-size-fits-all approach

Leaders who communicate the same way with every staff member risk alienating parts of the team. For example, a highly task-oriented leader who provides detailed process instructions may frustrate active, people-oriented staff who prefer collaboration and fast progress.

Undermining trust through overcorrection

Offering support without understanding personal preferences can backfire. A staff member who values independence may perceive “checking in” as micromanagement, reducing trust and morale.

Performance driven only by compliance

When leaders fail to adapt to personality differences, performance may default to meeting the bare minimum. Staff are less likely to offer discretionary effort if they feel unseen or undervalued.

These pitfalls highlight why awareness of others is not a “nice-to-have” but an essential leadership skill in pharmacy practice.

Conclusion

While reading minds may remain in the realm of fiction, emotionally intelligent leaders possess a very real “superpower” in the form of awareness, emotional reasoning, and the ability to inspire performance. In pharmacy practice, these skills are not simply about smoother communication—they underpin safer, more effective teamwork, improved patient outcomes, and a resilient, adaptable workforce 6.

Leaders who cultivate emotional intelligence create environments where staff feel seen, understood, and supported. Misunderstandings are minimised, conflicts are constructively managed, and performance is elevated beyond mere compliance. By adapting leadership style to personality differences and demonstrating empathy alongside accountability, leaders foster trust, engagement, and discretionary effort.

In a sector where precision, safety, and patient relationships are paramount, emotionally intelligent leadership is not optional—it is essential. The human superpower of emotional intelligence equips pharmacy leaders to navigate complexity, inspire teams, and deliver exceptional care, proving that the real magic in pharmacy is rooted in understanding, connection, and thoughtful action.

Australia

Competencies addressed: 2.2, 2.3, 4.1, 4.3, 4.6

Accreditation Expires: 31/10/2027

Accreditation Number: A2511AUP1

This activity has been accredited for 0.75 hour of Group Two CPD (or 1.5 CPD credits) suitable for inclusion in an individual pharmacists CPD plan upon successful completion of the associated assessment activity.

New Zealand

This article aims to equip you with the tools necessary to meet recertification requirements and actively contribute to the growth of your professional knowledge and skills.

Effectively contribute to your annual recertification by utilising this content to document diverse learning activities, regardless of whether this topic was included in your professional development plan.

References

- Genos International. Emotional Intelligence. Genos International. [Online] 24 July 2025. https://www.genosinternational.com/emotional-intelligence.

- Toth, Csaba. Uncommon Sense in Unusual Times. s.l.: Authorsunite, 2020.

- ICQ Global. Cultural Intelligence. ICQ Global. Online 18 August 2025.

- Global DISC Report. s.l.: ICQ Global, 2023.

- Intercultural DISC™ Leveraging Personal and Cultural Differences Licensed Practitioner Training Module 3 DISC. 16 June 2018.

- Evidence and Strategies for Including Emotional Intelligence in Pharmacy Education. Butler, Lakesha, et al. 2022, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, pp. 1095 - 1113.

- A Cross-Cectional Study Compaing Emotional Intelligence and Perceived Stress Amongst Community Pharmacists Deliverying and Not Delivering a New Service. Sencanski, Dejan, Marinkovic, Valentina and Tadic, Ivana. 2023, International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, pp. 45:1136-1143.

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd. National Competency Standards Framework for Pharmacists in Australia 2016. Canberra: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd., 2016.