Introduction

Shingles is the term given colloquially to herpes zoster and is associated with a painful, self-limiting vesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution1-3. It may be preceded by systemic symptoms, and presentation may share features with other dermatological presentations. Early identification and treatment of shingles is vital to minimise discomfort and potentially serious complications, including ongoing pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia. Pharmacists play an important role in all jurisdictions assisting with recognition and referral, alongside provision of supportive measures. In some jurisdictions pharmacists may also diagnose shingles and prescribe or supply antiviral medications4-6. This article follows on from our ‘Impetigo in brief’ article and provides a brief overview of the management of shingles and the role of that pharmacists can play.

Shingles1-5

Shingles is the reactivation of previously dormant infection with varicella zoster. Following recovery from acute infection with the varicella zoster virus, the virus remains dormant in the dorsal root ganglion.1-2

Reinfection is prevented primarily by a competent immune system. In situations where the immune system response is reduced the virus may overwhelm the immune system and cause an acute infection of the peripheral nervous system.1-2

As such herpes zoster infection requires exposure to varicella zoster, which is common in Australia, particularly in the over 50 years cohort.3 There do not appear to be clear-cut precipitating factors2, although some sources suggest triggering factors such as infection, injury or emotional stress.1,7

The prevalence of HZ, and the severity of infection increases with age3 potentially due to age-related immune decline, among other factors. The lifetime risk of HZ for people who live to 80 years of age is around 50%.3 This trend to increasing incidence with increasing age is seen in several developed countries.8

In Australia, there are approximately 560 cases of HZ per 100,000 people per year across all age groups.3

Complications

Complications have been estimated to occur in between 13 to 26% of people with herpes zoster.3 The incidence and severity of complications is noted to increase with increasing age.3

The most common complication is post-herpetic neuralgia, which occurs more frequently in older adults.

Other complications include:

- Secondary infection of lesions

- Scarring

- Pneumonia

- Infections involving other body systems such as the eye (herpes opthalmicus), ear (herpes oticus) or broader central nervous system and viscera (disseminated herpes zoster)

Presentation and differential diagnosis1-5,7

The hallmark of herpes zoster infection is a vesicular rash, on an erythematous base, in a unilateral dermatomal distribution (following a line along the dermatomes of the peripheral nervous system).1,2

HZ presents with prodromal symptoms and localised discomfort in the area approximately 1-3 days prior to the eruption of the characteristic rash.

Prodromal symptoms include:

- Localised nerve pain (described as burning)

- Lethargy, fever, headache

- Abnormal skin sensations

- Lethargy, fever, headache

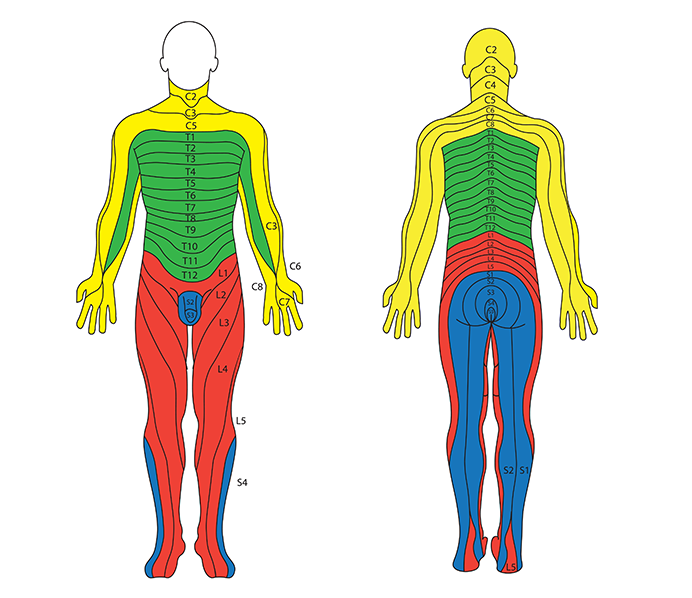

Once the rash erupts, it will typically be a crop of red papules. These are typically unilateral along a dermatomal line (see image 2 for a reminder on dermatome locations). Some lesions may appear outside of this area (satellite lesions).

Fluid-filled vesicles may continue to erupt for 3-5 days, becoming pustular and then scabbing over around 7-10 days after the initial lesions occurred.

The most common location for herpes zoster rash is the chest, neck, forehead or lower back (sacral/lumbar nerve supply regions). When nerves close to the eye or ear are involved, there are additional considerations.

Involvement of the trigeminal nerve will present with blistering around the eye and/or eyelid with pain, redness and swelling. This is referred to as herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

Involvement of the vestibulocochlear nerve presents with earache and blistering in and around the ear canal, with or without facial involvement. This is referred to as herpes zoster oticus/Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

Involvement of the central nervous system or other viscera (heart, lungs etc) is referred to as disseminated herpes zoster. It occurs more frequently in immunocompromised patients.

Diagnosis and patient history

Diagnosis is based on patient history and examination of the rash rather than laboratory confirmation. It may be required in situations where the diagnosis is uncertain, or where the patient does not recall previous exposure to varicella zoster.

A comprehensive patient history should be taken as part of the diagnosis and to assess the safety and appropriateness of potential treatment.

This should include:4

- Age

- Pregnancy and/or lactation status

- Nature, severity, and frequency of symptoms

- Nature of rash (examination recommended to confirm), distribution, appearance and number of lesions

- Onset and duration

- Precipitating and relieving factors

- History of past varicella zoster infection

- Underlying medical conditions

- Current and recently ceased treatments

- Strategies used to treat current symptoms and response

- Allergies or adverse reactions experienced previously

- Immunisation status for varicella and herpes zoster

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include other viral infections (herpes simplex, primary varicella zoster), impetigo, contact dermatitis, and insect bites.7

Herpes zoster | Varicella zoster10 | Primary Herpes Simplex 111 | Insect bites12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Appearance | Fluid filled vesicles with an erythematous base | Red papules progressing to vesicles | White vesicles that evolve to yellowish ulcers (primary) Small closely grouped vesicles (recurrent) | Small blister or cluster of blisters with surrounding erythema |

Itch | Possible, more commonly burning sensation | Very itchy and uncomfortable | Prior to vesicle appearance (recurrent) | Itch and burning sensation |

Location | Unilateral, along dermatomes | Variable | Tongue, throat, palette, inside cheeks. Recurrent – face and lips | Variable |

Patient features | Older adults more common | Most cases in children under 10 years old | Children | Variable |

Other symptoms | Tingling, burning sensation. May experience prior to rash eruption | May experience high fever, headache, cold-like symptoms, vomiting and diarrhoea | Fever, difficulty eating | N/A |

Red flag symptoms4,5

Early treatment of shingles is key to prevention of complications, and it may be appropriate to treat concurrently with referral.

Note: the specifics of which populations must be immediately referred, or that pharmacists may treat and refer, are dictated by the legislative instruments and protocols associated with pharmacist prescribing and supply in the jurisdiction. Pharmacists are reminded to adhere to their jurisdictional requirements.

Referral is required in the following situations, although providing treatment alongside referral may be appropriate and permitted in some jurisdictions:

- Patient is immunocompromised

- Superinfection of lesions is present*

- Multi-dermatomal rash or disseminated zoster*

- Complications are present (eg. postherpetic neuralgia)*

- Rash affecting the face or genital area*

- Pain management is required beyond mild pain*

- Patient is pregnant (known history of varicella zoster)*

- Inadequate response to treatment

- Previous vaccination against herpes zoster

- Patient is breastfeeding a neonate5 (note that to protect older breastfed babies the rash should be covered)

- Complications suspected (scarring, pneumonia, neurological complications)*

- Rash present for > 72 hours

- Early presentation of pain prior to rash onset5

This is not an exhaustive list.

*Immediate referral required in some jurisdictions

Urgent referral to the emergency department is recommended in situations where the eye and/or ear are involved (Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus or Herpes Zoster Oticus).4,5

Treatment4,5,13

Pharmacological management of herpes zoster includes antiviral therapy and pain management. Symptoms are usually self-limiting, but the use of antiviral therapy is indicated if commenced early enough.

Antiviral treatment can reduce symptoms including acute pain, rash duration, viral shedding, and the risk of complications if started within 72 hours of rash onset.4 For immunocompromised patients, initiation of antiviral treatment reduces complications at any stage of rash duration.4

As such, antiviral treatment is indicated for the treatment of adults:13

- Immunocompetent adults who present within 72 hours of rash eruption

- Adults with immune compromise at any stage following rash eruption

Antiviral therapy should commence as soon as possible with:13

| 1. Valaciclovir OR | 1g orally, every 8 hours for 7 days Child 2 years or older: 20mg/kg up to 1g |

|---|---|

| 1. Famciclovir OR | 500mg orally, every 8 hours for 7 days Dose adjustment required in adults with kidney impairment |

| 2. Aciclovir* | 800mg orally, 5 times per day for 7 days |

*Famciclovir and valaciclovir may be more effective in reducing acute pain in adults with shingles and are considered first line. There is insufficient data to support use of famciclovir in pregnancy, and limited data to suggest valaciclovir may be safe in pregnancy.

Intravenous antiviral therapy is recommended for shingles in situations of disseminated disease, invasive disease, and nerve involvement of the eye or ear (herpes zoster opthalmicus and herpes zoster oticus).13 As previously noted, these presentations warrant immediate referral.

Pain management14

Mild shingles pain can be managed with oral paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

Ice packs may also be useful.

Neuropathic pain can be treated with lidocaine 5% patches, provided the area has no broken skin or lesions. This limits the usefulness of this treatment in an acute presentation.

Ongoing neuropathic pain (post-herpetic neuralgia) may be treated similarly to other neuropathic pain.

Non-pharmacological management advice8,9

Non-pharmacological management includes avoiding irritation and preventing infection by strategies such as:

- Wearing loose clothing

- Keeping the area clean and dry

- Using a cooled towel on the area

- Covering the rash to avoid transmission

Covering of the lesions is recommended to reduce transmission, as herpes zoster is infectious to those who have not previously been infected with varicella zoster.4,5,10

Vaccination against herpes zoster is recommended as the primary prevention strategy. Vaccination is recommended for people at moderate to high risk of severe illness and complications for shingles.

The Australia Immunisation Handbook recommends vaccination for:3

- People aged 50 and over (NIP funded 65 and over)

- Immunocompromised people aged 18 and over

- People aged 50 and over, living in a household with someone with a weakened immune system.

Role of the pharmacist in Australia

Pharmacists have traditionally played a supportive role in the treatment of herpes zoster by providing referral, advice on preventing transmission, and counselling. In recent years expansion of scope of practice has allowed for appropriately trained pharmacists to provide treatment with schedule 4 medicines to eligible patients under various state and territory trials and pilots.

At time of writing, appropriately trained pharmacists in Queensland and Victoria can provide antiviral treatment to adult patients (over the age of 18) with shingles under the Community Pharmacy Scope of Practice Program and the Community Pharmacist Program respectively. New South Wales allows provision of antiviral treatment under the NSW Pharmacy Trial, due to conclude 31 August 2025.6

Other jurisdictions have expressed their intentions to include management of herpes zoster as their individual programs roll out.

Each jurisdiction has specific eligibility requirements for patient inclusions, with referral to a medical practitioner recommended for patients with red flag clinical features and those at high risk of serious complications.

In Queensland, pharmacists can prescribe oral antiviral therapy and oral analgesia for mild shingles pain (non-neuropathic pain) in accordance with the Therapeutic Guidelines.4

Victorian and New South Wales pharmacists are permitted to dispense antiviral medications and non-prescription analgesia as per protocol.5,6

Conclusion

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of herpes zoster decreases the likelihood of experiencing lasting complications.

Pharmacists can play a greater role in the diagnosis and management of herpes zoster under expansion of scope of practice. An understanding of symptoms, management and referral requirements remains important for pharmacists in all areas of practice.

A thorough history can assist pharmacists to appropriately diagnose or refer patients in a timely manner and should be undertaken wherever possible. Appropriate use of antivirals within the first 72 hours of presentation is vital to management, and pharmacists should prescribe/supply or refer within that period wherever possible.

Pharmacists in all areas of practice can support patients and carers with non-pharmacological advice and referral for further treatment.

Accreditation Number: A2509AUP3

This activity has been accredited for 0.75 hr of Group 1 CPD (or 0.75 CPD credit) suitable for inclusion in an individual pharmacist’s CPD plan which can be converted to 0.75 hr of Group 2 CPD (or 1.5 CPD credits) upon successful completion of relevant assessment activities.

Pharmacist Competencies: 1.3, 1.5, 2.2, 2.3, 3.1, 3.2, 3.5

References

- Quirke K, Oakley A. Herpes Zoster [Internet]. Auckland (NZ): DermNet New Zealand Trust; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/impetigo

- Kay K. Shingles (Herpes Zoster) [Internet]. Rahway (NJ): Merck & Co. Inc.; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/herpesviruses/herpes-zoster

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Herpes Zoster. In: Australian Immunisation Handbook [Internet]. Canberra (AU): Department of Health; 2025 Feb [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine-preventable-diseases/zoster-herpes-zoster

- Queensland Health. Herpes Zoster (Shingles) – Clinical Practice Guideline [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Queensland Health; 2025 Jul [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/1304392/herpes-zoster-shingles-guideline.pdf

- Victorian Department of Health. Protocol for Management of Herpes Zoster (Shingles) [Internet]. Melbourne (AU): Victorian Community Pharmacist Statewide Pilot; 2024 Feb [cited 2025 Aug].

- NSW Ministry of Health. Authority – Supply of restricted substances by pharmacists. Sydney: NSW Health; 2025 Jun 25 [cited 2025 Aug 22].

- Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes Zoster [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan– [updated 2023 Sep 4; cited 2025 Aug 22]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

- Curran D, Doherty TM, Lecrenier N, Breuer T. Healthy ageing: Herpes zoster infection and the role of zoster vaccination. NPJ Vaccines. 2023;8(1):184. doi:10.1038/s41541-023-00757-0

- Crawford NW, Buttery JP, Marshall HS, McIntyre PB. Zoster (herpes zoster) [Internet]. Melbourne (AU): Melbourne Vaccine Education Centre; [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://mvec.mcri.edu.au/references/zoster/

- Ngan V, Gomez J, Dedat A, Coulson I. Chickenpox (Varicella) [Internet]. Auckland (NZ): DermNet New Zealand Trust; 2002 [updated 2022 Jul; cited 2025 Aug 22]. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/chickenpox

- Oakley A, Morrison C. Herpes Simplex [Internet]. Auckland (NZ): DermNet New Zealand Trust; 2015 [cited 2024 Sep]. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/herpes-simplex

- Healthdirect Australia. Insect bites and stings [Internet]. Canberra (AU): Healthdirect; [cited 2025 Aug 22]. Available from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/insect-bites-and-sting

- Therapeutic Guidelines Limited. Shingles (herpes zoster) [Internet]. Melbourne (AU): eTG complete; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://app.tg.org.au/viewTopic?etgAccess=true&guidelinePage=Antibiotic&topicfile=bartonella-infections&guidelinename=auto§ionId=c_ABG_Shingles-herpes-zoster_topic_3#c_ABG_Shingles-herpes-zoster_topic_3

- Health Direct. Shingles [Internet]. Canberra (AU): Health Direct; [cited 2025 Aug]. Available from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/shingles