Introduction

Obesity and becoming overweight continue to be major public health concerns in Australia, with significant and growing health and economic consequences.

In 2022, two-thirds of adults aged 18 and over were living with overweight or obesity, a rate that has remained stable since 2017 but represents a substantial increase since the 1990s 1.

The challenge is not limited to adults — one in four children and adolescents aged two to 17 were also classified as overweight or obese in 2022, however this figure has steadily climbed over the past three decades.

There are marked disparities across different population groups. First Nations peoples are disproportionately affected, with 74 percent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults and 38 percent of children aged 2–17 are living with overweight or obesity. Prevalence is also influenced by geography: people living in inner regional (68 percent) and outer regional/remote areas (70 percent) are more likely to be affected compared to their metropolitan counterparts (64 percent)1.

The health consequences of excess body weight can be grave. Carrying extra adipose tissue increases the risk of chronic conditions such as stroke, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, and several types of cancer, including colon, breast, and endometrial cancers 2. It also contributes to poor mental health, reduced mobility, increased medication use, and diminished quality of life. As a result, overweight and obesity are among the leading contributors to preventable illness, hospitalisations, and healthcare costs in Australia 3.

Despite the complexity of weight-related issues, even modest weight loss (five to 10 percent) can significantly improve metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes 4. Community pharmacists are uniquely positioned to provide early identification, education, and ongoing support for people living with overweight or obesity.

With frequent patient contact, clinical expertise, and increasing involvement in primary care services, pharmacists can offer both lifestyle and pharmacological interventions, help reduce the burden of chronic disease, and support sustainable health behaviour change.

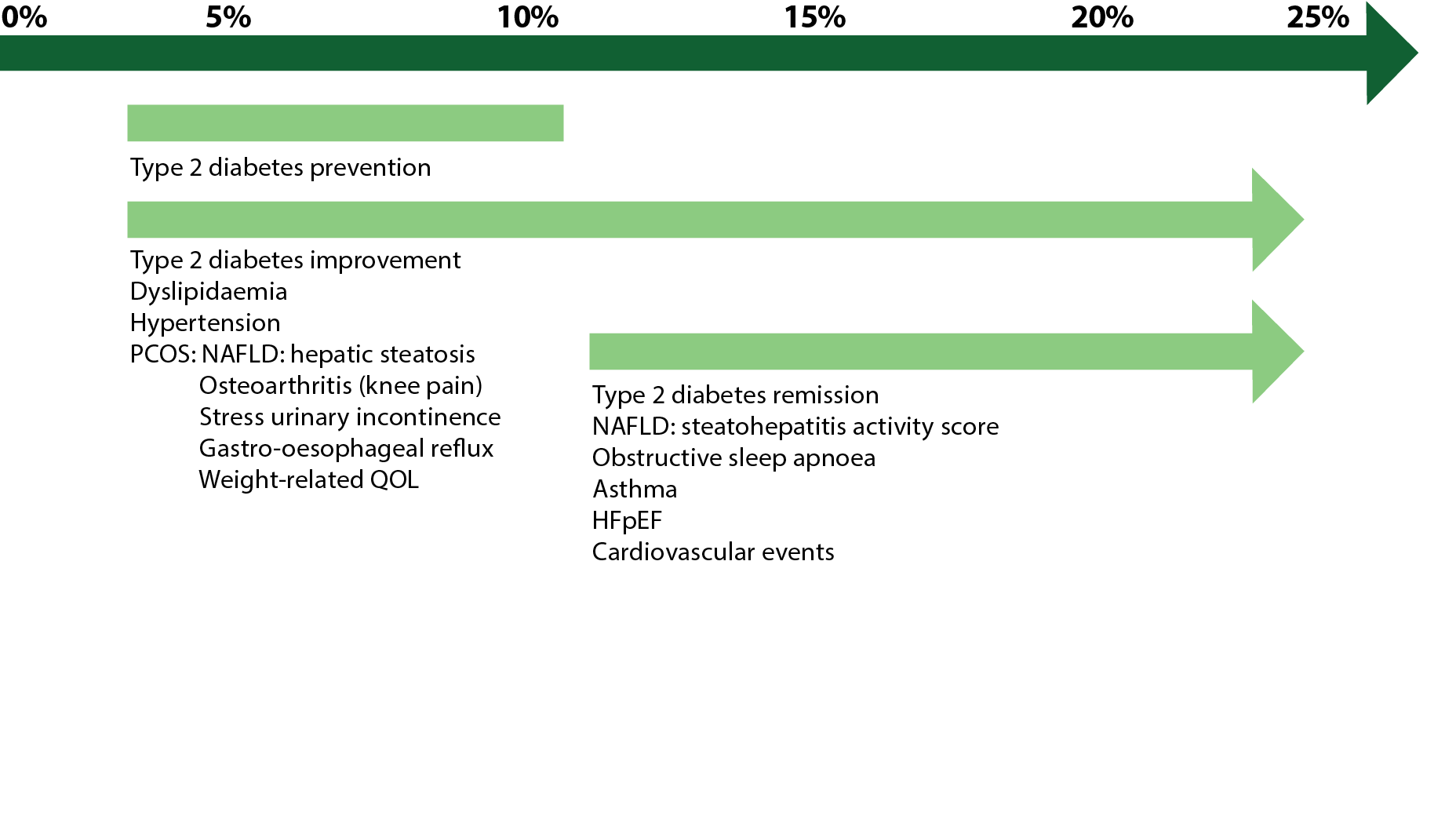

Magnitude of weight loss required for improvement in obesity complications 5

This article 5 explores the multifaceted approach required for obesity management, emphasising evidence-based, person-centred weight management services that combine clinical insight, medication management, and lifestyle advice. These aspects present opportunities for pharmacists to consider in delivering this service.

Definition and classification

In Australia, overweight and obesity are measured primarily using Body Mass Index (BMI), a simple tool calculated by dividing a person’s weight (in kilograms) by their height (in metres squared). While not a perfect measure, BMI remains a practical, low-cost screening tool in primary care, including pharmacy settings and medical centres.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and Department of Health and Aged Care guidelines, adults are classified as 6:

| BMI (Adults) | Classification |

|---|---|

| Less than 18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5 to 24.9 | Healthy weight |

| 25 to 29.9 | Overweight but not obese |

| 30 to 34.9 | Obese class I |

| 35 - 39.9 | Obese class II |

| 40 or more | Obese class III |

To complement BMI, waist circumference is recommended for assessing abdominal (visceral) fat, which is more strongly linked to cardiometabolic risk. Health risk is increased at 6:

| Gender | Increased risk | Greatly increased risk |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 94cm or more | 102cm or more |

| Women | 80cm or more | 88cm or more |

Pharmacists play a critical role in early detection and engagement. By incorporating BMI and waist circumference into everyday consultations such as medication reviews or chronic disease support, pharmacists can help initiate conversations, guide behaviour change, and refer patients to appropriate services.

Causes

The cause of overweight and obesity are multifactorial and complex. They are influenced by a host of biological, environmental, behavioural and social factors. Simply put, it results from a sustained positive energy balance—where energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. Unfortunately, it isn’t quite so straightforward. Genetic predisposition, altered metabolism, gut microbiota, hormonal imbalances, and certain medications can all contribute to weight gain 7.

Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, overweight and obesity are strongly influenced by food insecurity, geographic location, and broader social determinants of health. Many communities, particularly in rural and remote regions, have limited access to affordable, nutritious food and rely on energy-dense, processed options. Socioeconomic disadvantage, overcrowded housing, reduced access to healthcare, and fewer opportunities for physical activity further contribute to risk. These factors are shaped by ongoing impacts of colonisation and systemic inequity 7. For pharmacists, recognising these structural barriers is essential to providing respectful, culturally safe care and supporting holistic, community-driven health solutions.

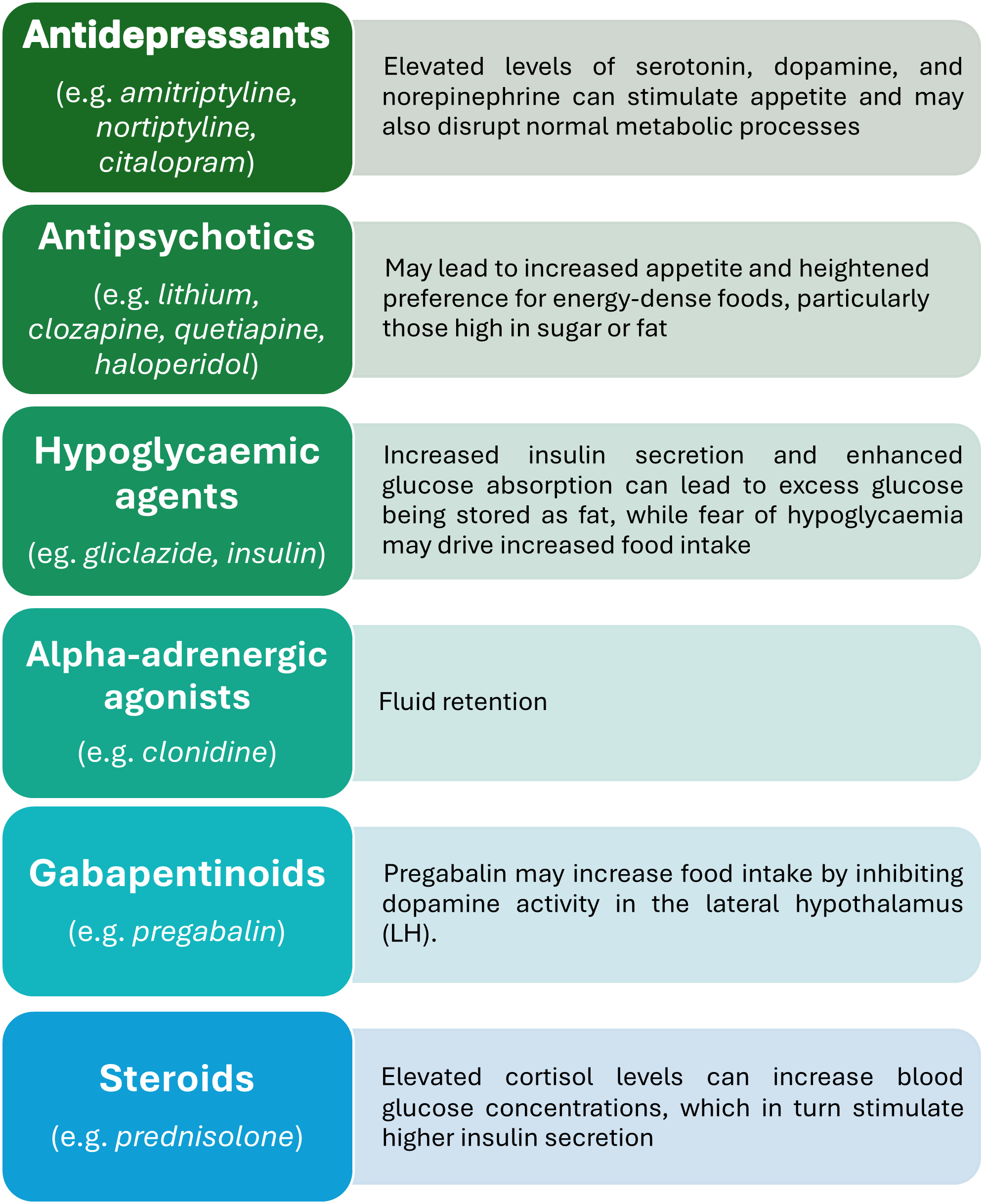

Medications that contribute to weight gain 8-12

Management

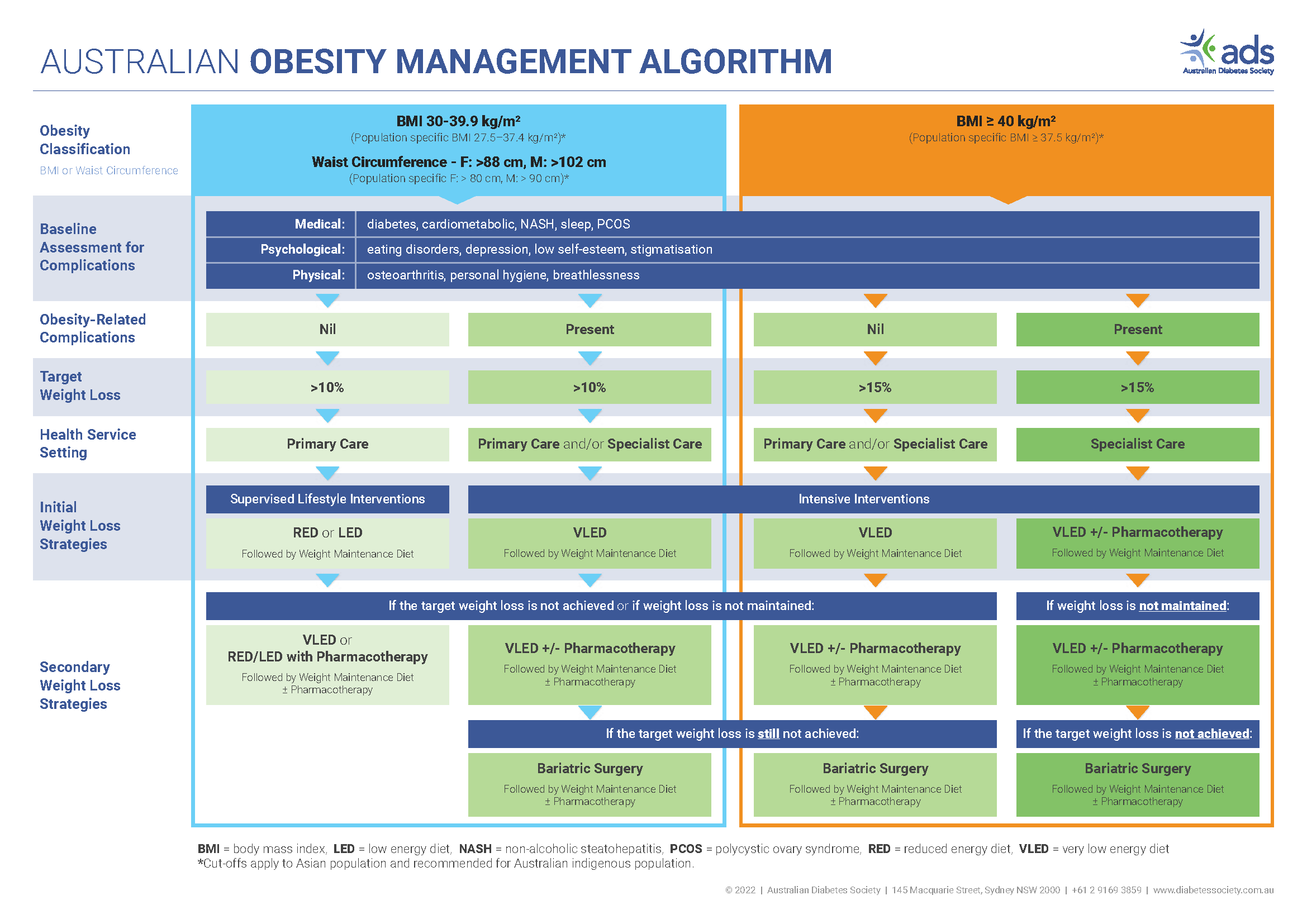

According to the Australian Obesity Management Algorithm and NHMRC guidelines, treatment of obesity begins with non-pharmacological strategies such as dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioural interventions, including goal-setting and psychological support 13. These lifestyle changes are considered first-line therapy and should be tailored to individual needs. For patients who do not achieve sufficient weight loss through lifestyle alone, pharmacological options like GLP-1 receptor agonists may be considered, especially in those with obesity-related comorbidities. Treatment decisions should be guided by BMI, risk profile, and patient preferences, with ongoing monitoring and support in primary care.

Figure 6: Australian Diabetes Society. Australian Obesity Management Algorithm 202214

Non-pharmacological

Non-pharmacological management of obesity is foundational to effective long-term weight control and involves a multifaceted approach targeting lifestyle, behaviour, and environmental factors. Pharmacists play a vital role in supporting supervised lifestyle interventions, which are central to all weight management strategies. Key treatment goals include reducing overall energy intake, improving diet quality, and promoting increased physical activity. It’s important to recognise that a high-energy diet does not necessarily meet nutritional needs, and pharmacists should consider the adequacy of a patient’s nutrient intake when offering dietary guidance 13.

Collaborating with a multidisciplinary team, including accredited practising dietitians, exercise physiologists, and psychologists can enhance patient outcomes and provide comprehensive support tailored to individual needs.

Dietary modification

Weight management is influenced by several interrelated dietary factors, including total energy intake, macronutrient composition, and meal timing. Evidence-based strategies highlight that achieving an energy deficit is the primary driver of weight loss. This can typically be accomplished through a low-calorie diet, often with reduced fat or carbohydrate content. In certain cases, a very-low-calorie diet may be appropriate for short-term use under professional supervision 13.

Diets that manipulate macronutrient ratios — such as ketogenic or high-protein regimens—may be considered for specific individuals.

However, the long-term safety, sustainability, and overall efficacy of these approaches remain uncertain.

Clinical judgement should be applied when evaluating the suitability of such diets, taking into account individual metabolic profiles, comorbidities, and patient preferences 15.

Energy deficit and reducing energy intake options include 13:

| RED | Reduced Energy Diet |

|

|---|---|---|

| LED | Low Energy Diet |

|

| VLED | Very Low Energy Diet |

Contraindications

|

Medication changes required for VLED

Physical activity

Regular physical activity is a key component of managing obesity and improving overall health. National guidelines recommend that all adults engage in consistent physical activity, with both aerobic and resistance-based exercises offering distinct benefits. Resistance training helps preserve and enhance muscle mass and strength, reducing the risk of sarcopenia, while aerobic activity supports cardiovascular fitness and metabolic health 16, 17.

Adaptations may be necessary for individuals with musculoskeletal limitations, for whom low-impact options like aquatic exercise can be beneficial. Similarly, those with cardiovascular or respiratory conditions may require modified, lower-intensity regimens. Referral to an accredited exercise physiologist or participation in structured community-based programs can provide tailored support and improve adherence to physical activity interventions 17.

Behavioural interventions

Behavioural interventions aim to support sustainable lifestyle changes through structured strategies such as goal setting, self-monitoring, problem-solving, and motivational interviewing. These interventions often include dietary and physical activity components, delivered via individual or group-based programs, and may be enhanced through digital platforms or community support. Evidence from systematic reviews shows that behavioural weight management interventions in primary care settings can lead to clinically meaningful weight loss, with average reductions of 2–3 kg sustained over 12–24 months 18.

Great government funded programs that might be available in your state to assist in your consumers' behavioural change include:

| Program | State |

|---|---|

| Life! | Victoria |

| My Health for Life | Queensland |

| Get Healthy Service | New South Wales |

| COACH Program | Tasmania |

| Better Health Coaching Service | South Australia Western Australia |

Pharmacological intervention

Pharmacological therapy is an important adjunct in the management of obesity, particularly for individuals who have not achieved sufficient weight loss through lifestyle interventions alone. In Australia, medications are typically indicated for adults with a BMI ≥30 kg/m², or ≥27 kg/m² with obesity-related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, or obstructive sleep apnoea 5, 19.

These agents work through various mechanisms, including appetite suppression, delayed gastric emptying, and modulation of energy balance. While modest weight reductions of five to 15 percent are achievable, the choice of therapy should be guided by individual risk factors, tolerability, cost, and long-term safety.

Pharmacotherapy is most effective when integrated into a broader, multidisciplinary approach that includes dietary, physical, and behavioural support 20.

| Name | MoA | Starting Dose | Side Effects / Contradictions | Potential Weight Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide 21 - Wegovy | GLP-1 analogue: Enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon release, reduces appetite, and slows gastric emptying | 0.25 mg weekly up to 2.4 mg | Nausea, vomiting, GI upset, GORD, hypoglycaemia (when used with SU or insulin), injection site reactions, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, flatulence CI: Pregnancy, medullary thyroid cancer and MEN-2 (liraglutide) | 10 –15% |

| Liraglutide 22 - Sexenda | 0.6 mg daily up to 3 mg daily | 6% | ||

| Tirzepatide 23 - Mounjaro | GIP/GLP-1 dual agonist: Enhances insulin sensitivity and promotes glucosedependent insulin release, while suppressing glucagon secretion. It also slows gastric emptying, thereby delaying glucose absorption, and contributes to appetite reduction. | 2.5 mg weekly | As above | 15 – 20% |

| Naltrexone/Buproprion 19, 24 - Contrave 8/90 | Modulates neural pathways involved in appetite control within the hypothalamus and influences reward-driven eating behaviours via the mesolimbic dopamine system | 8 mg / 90 mg | GI upset, headache, dizziness, seizures, risk of opioid overdose, suicidal thoughts, depression, hepatotoxicity, glaucoma CI: hypersensitivity, uncontrolled hypertension, seizure disorder, acute alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal, severe hepatic impairment, end stage renal failure, MAOI use | 5% |

| Phentermine 25 | Centrally acting adrenergic agonist that suppresses appetite. | 15 mg daily | Dry mouth, constipation, sleeplessness, hypertension, closed angle glaucoma, euphoria, diarrhoea, rash, palpitations C/I: severe hypertension, heart murmur, arrythmia, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, psychiatric illness, MAOI or SSRI use in 14 days, pregnancy, breastfeeding | 6% |

| Orlistat 19, 26 | Gastric and pancreatic lipase inhibitor which inhibits absorption of fat from diet | 120 mg three times daily | Flatulence, steatorrhoea, deficiency in A, D, E and K vitamins (fat soluble), stomach pain C/I: Pregnancy, malabsorption | 3 – 8% |

Bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery is recognised as the most effective long-term treatment for obesity, offering sustained weight loss and significant improvement or resolution of obesity-related comorbidities, particularly type 2 diabetes 27.

In Australia, the most commonly performed procedures include sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), with SG accounting for 80 percent of surgeries in 2023. These procedures typically result in an initial total weight loss (TWL) of around 30 percent, with long-term maintenance of 23–27 percent TWL at five years 27.

The surgery is recommended for individuals with a BMI ≥35 kg/m², or ≥30 kg/m² with type 2 diabetes, and may be considered for those with lower BMI if non-surgical methods have failed 28.

Pharmacist role

Community pharmacists are increasingly recognised as vital contributors to obesity care, offering accessible, evidence-based support within the primary healthcare system. To translate this potential into practice, pharmacists can adopt a structured, patient-centred approach 29, 30:

- Ask: Initiate respectful conversations by asking patients if they would like to discuss weight management and personal health goals.

- Assess: Measure BMI, waist circumference, and consider obesity-related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnoea.

- Advise: Educate patients on the health benefits of achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, including improved cardiovascular health, glycaemic control, and reduced medication burden.

- Assist: Support patients with weight management strategies, including lifestyle counselling, pharmacotherapy options, and referrals to dietitians, GPs, or bariatric specialists, through GP referral, when indicated.

- Arrange: Establish a plan for regular review and monitoring, ensuring continuity of care and adjustment of interventions based on progress and patient feedback.

Recent initiatives 29 have demonstrated the effectiveness of structured, pharmacy-led obesity management programs in community settings. These models emphasise the pharmacist’s role in initiating weight-related conversations, conducting clinical assessments, and delivering tailored interventions. Importantly, they highlight the value of integrating pharmacists into multidisciplinary care teams, where they can coordinate referrals, monitor progress, and provide ongoing support.

A clear example is when community pharmacists dispense GLP-1 analogues (or dual incretins) for weight loss, counselling extends well beyond the medication itself. They can provide practical guidance on injection technique, timing, and storage, as well as strategies to manage common side effects such as nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort.

Pharmacists are also well placed to monitor for potential drug interactions, reinforce adherence, and provide education around the importance of lifestyle measures alongside pharmacotherapy. During recent medicine shortages, many patients had to pause therapy; pharmacists can support safe re-initiation by ensuring treatment is restarted at the lowest available dose to minimise adverse effects. By being accessible and knowledgeable, pharmacists help patients feel more confident in their treatment and improve long-term outcomes.

Emerging evidence highlights that weight loss from GLP-1 therapy can sometimes include loss of lean muscle mass, particularly when dietary protein intake is insufficient. Pharmacists can help identify patients at risk and encourage balanced nutrition, including adequate protein and resistance exercise. Where appropriate, referral to a dietitian for individualised dietary support can enhance results and help preserve muscle health alongside treatment, or an exercise physiologist for movement support.

Such programs have shown that with appropriate protocols, training, and collaboration, pharmacists can deliver measurable improvements in patient outcomes. They also reinforce the need for sustainable funding models and formal recognition of pharmacists as key providers in chronic disease management. As these approaches gain traction, they offer a blueprint for expanding the pharmacist’s scope in preventive health and chronic condition support.

Future

Obesity pharmacotherapy is entering a transformative phase, driven by the emergence of multi-receptor agonists that mimic and amplify the effects of gut-derived hormones.

Among the most promising innovations are triple agonists—agents that simultaneously target GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors. Retatrutide, a leading candidate in this class, has demonstrated unprecedented weight loss outcomes in phase 2 trials, with up to 24.2 percent body weight reduction over 48 weeks in individuals without diabetes 31. These results rival those of bariatric surgery and mark a significant leap beyond earlier single and dual agonist therapies.

As these, and other, therapies progress through clinical development, they promise to reshape obesity management by offering potent, scalable alternatives to surgery 32. Pharmacists will play a critical role in this evolving landscape— supporting patient education, coordinating care, and reinforcing the importance of sustainable behavioural change alongside emerging medical treatments.

Australia

Competencies addressed: 1.5, 2.2, 2.3, 3.1, 3.2, 3.5, 3.6

Accreditation Expires: 31/10/2027

Accreditation Number: A2511AUP2

This activity has been accredited for 1.0 hr of Group 1 CPD (or 1.0 CPD credit) suitable for inclusion in an individual pharmacist’s CPD plan which can be converted to 1.0 hr of Group 2 CPD (or 2.0 CPD credits) upon successful completion of relevant assessment activities.

New Zealand

This article aims to equip you with the tools necessary to meet recertification requirements and actively contribute to the growth of your professional knowledge and skills.

Effectively contribute to your annual recertification by utilising this content to document diverse learning activities, regardless of whether this topic was included in your professional development plan.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and obesity: Australian Government; 2024 [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/overweight-and-obesity/contents/summary.

- World Health Organisation. Obesity: Health consequences of being overweight: WHO; 2024 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/obesity-health-consequences-of-being-overweight.

- Commonwealth of Australia. The National Obesity Strategy 2022-2032: At a Glance.: Health Ministers Meeting; 2022.

- Ryan DH, Yockey SR. Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5 percent, 10 percent, 15 percent, and Over. Current Obesity Reports. 2017;6(2):187-94.

- Walmsley R, Sumithran P. Current and emerging medications for the management of obesity in adults. MJA [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/6/current-and-emerging-medications-management-obesity-adults.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. BMI and waist 2024 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/overweight-and-obesity/bmi-and-waist.

- Masood B, Moorthy M. Causes of obesity: a review. Clinical Medicine. 2023;23(4):284-91.

- Fava M. Weight gain and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 11:37-41.

- Russell-Jones D, Khan R. Insulin-associated weight gain in diabetes--causes, effects and coping strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(6):799-812.

- Bryson CM, Psaty BMMDPBM. A Review of the Adverse Effects of Peripheral Alpha-1 Antagonists in Hypertension Therapy. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2002;3(1):7.

- Gammone MA, Efthymakis K, D'Orazio N. Effect of Third-Generation Beta Blockers on Weight Loss in a Population of Overweight-Obese Subjects in a Controlled Dietary Regimen. J Nutr Metab. 2021;2021:5767306.

- Ikeda H, Yonemochi N, Ardianto C, Yang L, Kamei J. Pregabalin increases food intake through dopaminergic systems in the hypothalamus. Brain Research. 2018;1701:219-26.

- Markovic TP, Proietto, J., Dixon, J. B., Rigas, G., Deed, G., Hamdorf, J. M., Bessell, E., Kizirian, N., Andrikopoulos, S., & Colagiuri, S. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm: A simple tool to guide the management of obesity in primary care: Australian Diabetes Society; 2025 [Available from: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Australian-Obesity-Management-Algorithm-August-2025.pdf.

- Australian Diabetes Society. Australian Obesity Management Algorithm [Diagram] 2022 [Available from: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/downloads/20220902 percent20Diagram percent20- percent20Australian percent20Obesity percent20Management percent20Algorithm percent202022 percent20.pdf.

- Kim JY. Optimal Diet Strategies for Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance. JOMES. 2021;30(1):20-31.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Physical Activity, 2011-12. Canberra: ABS; 2013.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity (SNAP): A population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. 2015.

- Madigan CD, Graham HE, Sturgiss E, Kettle VE, Gokal K, Biddle G, et al. Effectiveness of weight management interventions for adults delivered in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2022;377:e069719.

- Forner P, Hocking S. Pharmacotherapy for the management of overweight and obesity. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2025;54:196-201.

- Proietto J. Medicines for long-term obesity management. Australian Prescriber. 2022;45:38-40.

- Wilding JP, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(11):989-1002.

- Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(1):11-22.

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, Wharton S, Connery L, Alves B, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;387(3):205-16.

- Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, Still C, Wyatt H, Burns C, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity‐related risk factors (COR‐II). Obesity. 2013;21(5):935-43.

- Bays HE, Lazarus E, Primack C, Fitch A. Obesity pillars roundtable: Phentermine – Past, present, and future. Obesity Pillars. 2022;3:100024.

- Bansal A, Patel P, Al Khalili Y. Orlistat Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542202/.

- Shilton H. Bariatric surgery. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2025;54:202-6.

- Brown WA, Liem R, Al-Sabah S, Anvari M, Boza C, Cohen RV, et al. Metabolic Bariatric Surgery Across the IFSO Chapters: Key Insights on the Baseline Patient Demographics, Procedure Types, and Mortality from the Eighth IFSO Global Registry Report. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1764-77.

- Queensland Health. Management for Overweight and Obesity - Clinical Practice Guideline. Queensland Community Pharmacy [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/1304390/overweight-obesity-management-guideline.pdf.

- Wharton S, Lau D, Vallis M, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://obesitycanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Canadian-Adult-Obesity-CPG-Appendix-2-5As-Framework-for-Obesity-Management.pdf.

- Coskun T, Urva S, Roell WC, Qu H, Loghin C, Moyers JS, et al. LY3437943, a novel triple glucagon, GIP, and GLP-1 receptor agonist for glycemic control and weight loss: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Cell Metab. 2022;34(9):1234-47.e9.